The Sixth Avenue School

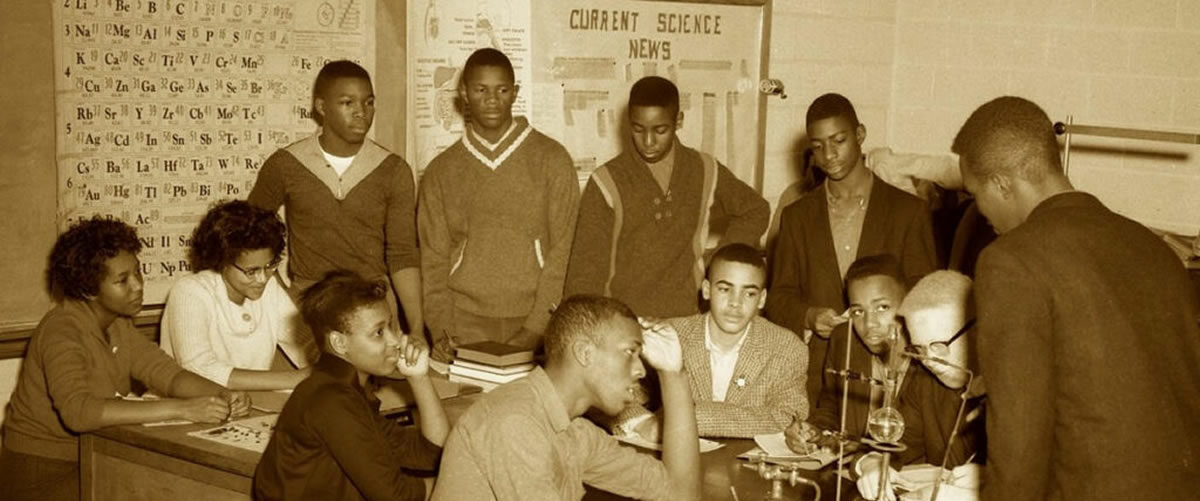

Although its resources were limited, the Sixth Avenue School had dedicated teachers. The school also served as a African-American community center from 1916 until l951.

The Sixth Avenue School was constructed at the northeast comer of Sixth Avenue and Valley Street in 1916 on one half acre of land that was bought for $700.00 from G. W. Justice. The new school replaced one that was located at Ninth and Justice Street, and for the year that it took for the school to be built, classes were held at the Star of Bethel Missionary Baptist Church. For 34 years Sixth Avenue School served not only as an educational center but as a community center as well, often hosting plays, dances, and community meetings. In 1916, Sixth Avenue had three teachers: W. M. Robinson (also the principal), Miss Hattie Butler, and Miss Teetie Sanders. Like his predecessor (Rev. Neil), Professor Robinson (as he was known) had to fulfill many roles. There was no janitor or central heating system, so Professor Robinson needed to be at school early to fire up the pot-bellied stoves, clean the rooms, and then assume his role as teacher and principal. (It was up to the teachers to see that the fires remained going during the day.) He served in his capacity as principal of Sixth Avenue until 1939 and during the years of his tenure he was a respected member of the community and a vocal and effective advocate for Blacks.

Professor Robinson is also remembered for his concern for the conditions of individuals in need. If Professor Robinson saw a need, either he would attend to it himself, or find someone who would. This is borne out by the recollections of Alberta Jowers, another pivotal figure in the history of the Black community in Henderson County. She recalled in a taped interview in 1986 that Professor Robinson would often send someone to her and she would attempt to meet the need. Not only was Professor Robinson a force in the Black community, he had influence in the wider community as well. French Broad Hustler editor M. D. Shipman kept Professor Robinson and the needs of Sixth Avenue School on the front page of his paper. He wrote editorials and articles on the educational system of the county and often ended with an appeal to the community-at-large to lend Robinson a hand.

The Sixth Avenue School building was a two-story frame structure that had classrooms on the ground floor and an auditorium that doubled as classrooms on the upper floor. The upper floor was divided into three classrooms separated from each other only by curtains. There had been no money in the Hendersonville school budget to erect permanent walls. The challenge that this presented to the teachers is summed up best by Mrs. Odell Rouse, who began her teaching career at Sixth Avenue School in 1926. She had to teach as many as 65 children at one time in one of the upper classrooms, and she explained that, “it wasn’t hard if you knew how to organize your work and give them something to do.” Another hardship for the students and teachers at that time was the lack of school bus transportation. This not only affected Black schools but White as well. A child either walked, which was customary, or someone gave the child a ride. It would not be until the mid 1940’s that county-wide bus transportation became a reality for any student in Henderson County.

The school year lasted only six months for Sixth Avenue students until, in 1936, through state- mandated regulations, the school year was extended to nine months. The State of North Carolina had already begun to set state-wide standards in education by 1933. In that year it took over from the local governments many of the responsibilities of education. “Separate but equal” remained in effect but now the state paid the salaries for both White and Black teachers. 1936 would also prove to be a pivotal year in Black education, for in that year the number of teachers at Sixth Avenue was increased from seven to nine and a high school curriculum was added and housed in a place called “the gym.”

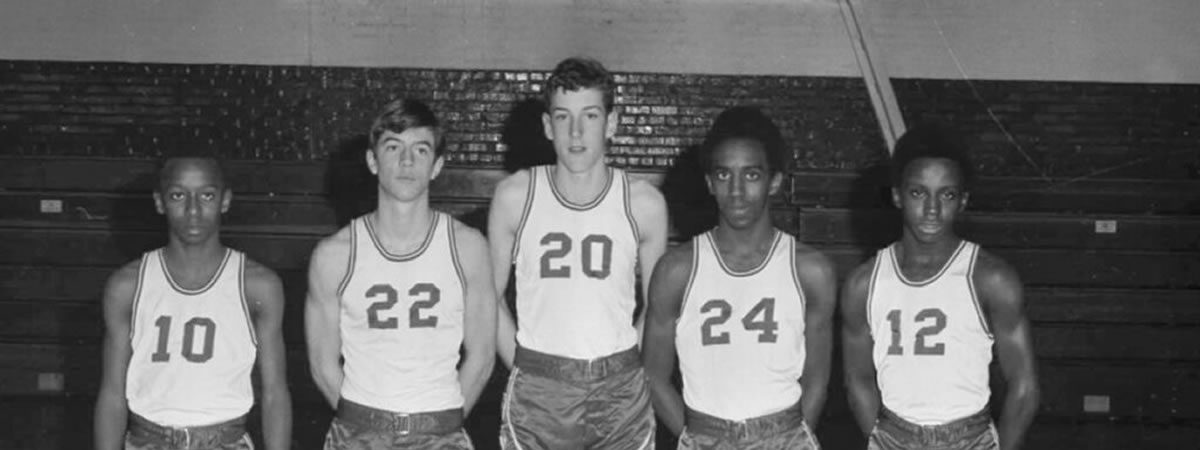

In 1936, during the Great Depression, a federally-funded works relief project built a new stone gymnasium for the Hendersonville High School, and the old wooden frame structure was dismantled and moved to a Ninth Avenue site to serve as a high school annex for the Sixth Avenue School. Dubbed “the gym,” it functioned as classrooms, auditorium, and gymnasium. Prior to 1936 there had been only sporadic high school education for Henderson County Blacks. In the early 1900’s Rev. Neill had lobbied hard for a high school and his requests were temporarily honored. But the commitment was half-hearted and in the years that followed the high school curriculum had been dropped. This left Black students without any opportunities for a high school education in Henderson County.

In order for a Black student to get a high school degree before 1936, he had to leave the county and attend a Black private school. Many high schools in the South were affiliated with Black colleges in order to fill this void in secondary education. Benedict College in Columbia, S.C., Tuskegee Institute, Tuskegee, Alabama, Barber Scotia Seminary College, Concord, N.C., The Allen School for Girls in Asheville, N.C., and Voorhees College in Denmark, S.C., are examples of places that offered a high school education. Some of these schools were church supported, like the Allen School for Girls that was supported by the Methodist Church, and therefore tuition was kept to a minimum. Scholarships were available and often these would be “working” scholarships, meaning that the student had to earn part of his or her room and board by working a campus job. Another way for Henderson County’s black students to earn tuition money was through summer employment. If a high school or college student came back to Henderson County during the summertime, there were often employment opportunities at places like The Woodfield Inn, Bonclarken, and the Skyland Hotel, where the tourist trade was brisk and the money was good. It should be noted, especially prior to 1936, that it took a very motivated and determined student to persevere in the educational climate of “separate but equal.”

In the years that Sixth Avenue School served the needs of Henderson County’s Black students, there was a steady increase in the quality of learning through the hiring of more teachers and the leadership of Professor Robinson. The school served the community well until 1951 when a new school for Blacks, Ninth Avenue School, was built. It is interesting to note that the Sixth Avenue School was sold by the city of Hendersonville and was renovated into private apartments. By 1982 the building had become so dilapidated that, at the request of the building owner, the old Sixth Avenue School was burned down by the Hendersonville fire department as a practice fire thus ending a significant chapter in the history of education for Blacks in Henderson County.

From A Brief History of the Black Presence in Henderson County by Gary Franklin Greene