The Ninth Avenue School

The Ninth Avenue School served African American students from Henderson, Polk and Transylvania counties from 1951 until 1965.

In May of 1950 a grant for “ninety-six thousand, six hundred dollars and twenty-nine cents from the School Plant Construction and Repair Fund of the State of North Carolina” was requested to fund the building of Ninth Avenue School. It was planned as a “union school,” a term for any school that included grades one through twelve within the same building.

When completed in 1951, it was the only remaining union school in Henderson County. The high school was on the second floor of the two story, red-brick building and the elementary grades occupied the first floor. It also served as a regional school for blacks, with students coming from three counties, Henderson, Transylvania, and Polk. This involved bussing students into the Ninth Avenue School, making some students, especially from Transylvania County, subject to excessively long bus rides. This would later become a passionate point of concern for the parents of the students from Brevard, but on Sunday, October 28, 1951, the dedication of Ninth Avenue School was a cause for celebration. The Community Choir sang two hymns, local ministers offered prayers and the school glee club added their own voices to the day by singing “There’s A Meeting Here Tonight”. Principal Marable served as Master of Ceremonies and the State Superintendent of Schools, Dr. Clyde A. Erwin, gave the keynote address. In the twilight of segregation there was a new beginning in education for black students in Henderson County.

Because Ninth Avenue was a consolidated school, the two remaining black schools that were still operating closed their doors. Both the East Flat Rock School, and the Brickton School, which was located in a small one-room schoolhouse in the Fletcher area of Henderson County, stopped operating at the end of the school term in 1952.

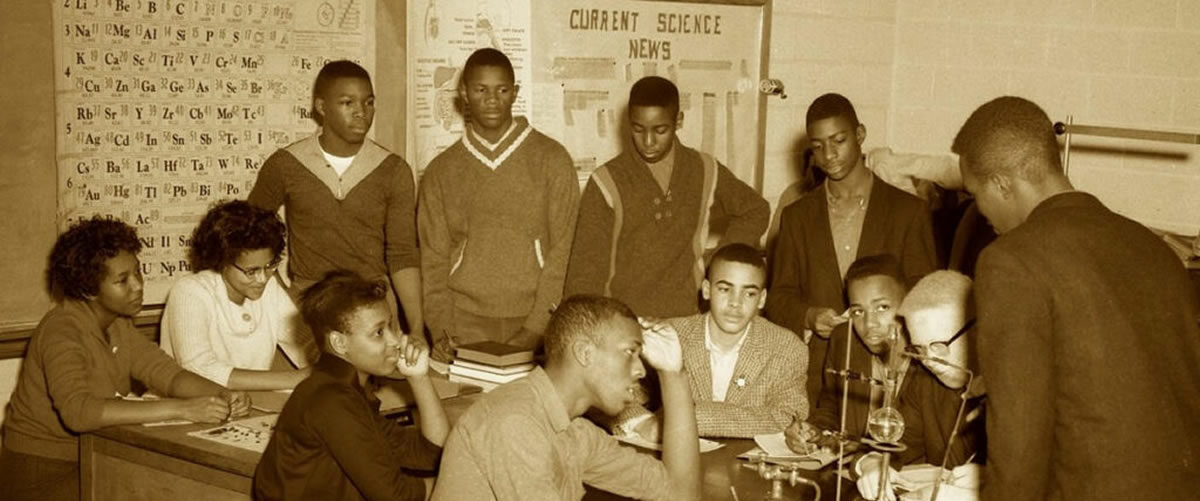

The building of Ninth Avenue School was sanctioned under the “separate but equal” clause of the State Constitution. Though substantial gains had been made in Black education over the six decades since the law was enacted, equality was still elusive. Black teachers in North Carolina weren’t comparably paid to their White counterparts and the financial allocation per student was less for Blacks than Whites. In Henderson County, for example, when the textbooks for Ninth Avenue Ninth Avenue were picked up at the school warehouse before the start of each school year, more often than not they would be hand-me-downs from the White schools. In spite of these inequities, the educational atmosphere at Ninth Avenue was, above all, caring, with the teachers and administrators compensating for the lack of resources with an almost family-like concern for their students. James Pilgrim, who served as chairman of the Ninth Avenue School Advisory Board, said of that time, “we felt like we had something going pretty nice. There were differences at the time, but there were differences in the city schools, too.” As a student at Ninth Avenue, Ruby Jackson Rivers remembers that the “parents were concerned; teachers were concerned. The teachers visited your home… and they knew where you lived… who your mother was… your dad was. Children respected the teachers and parents accepted the teacher’s word. (The teachers) were concerned with you… and made you get your work done.” Jessie Jenkins Wilson was a member of the last graduating class at Ninth Avenue and remembers that “the teachers really pushed me. The only thing that I was aware of was these teachers pushing me to develop to my full ability… that’s what I got out of Ninth Avenue” Ms. Mary Mims, who started teaching home economics at Ninth Avenue in 1948, recalls that “because we were lacking in so many areas, was the thing that drew us together… we might think that it was difficult then, but it didn’t hurt that much because we had a lot of togetherness, because the students and teachers worked much closer together….” Mrs. Odell Rouse was a good example of the type of teacher who exhibited concern. She taught first grade in the Black school system from 1926 until 1965, and after integration she taught special education at the Bruce Drysdale Elementary School until she retired in 1972. She said of Ninth Avenue that “it was like one big family.” Mrs. Rouse knew how to teach and keep the attention of her students. She was firm but caring and would go out of her way to see that the welfare of the child was attended to, often bringing something from home to help a child when needed. Because she taught for such a long time, it was not unusual for three generations in the same family to have had Mrs. Rouse as a teacher. In 1958 the students recognized her teaching skills by dedicating “The Tiger,” the Ninth Avenue yearbook, in her name. In the simply stated but heartfelt dedication, they thanked Mrs. Rouse for her “faithful years of teaching… for the confidence (she had) in students, and for the many extra special services (she gave) to students.”

In 1950 the Hendersonville School Board appointed an Advisory Board made up of prominent men from the Black community. The School Board was beginning to acknowledge that it would be necessary to have input from the Black community concerning areas of education that directly affected their children. The first year, two respected members of the Black community, Mr. James Pilgrim and Mr. James Mitchum, served in this capacity as non-voting members of the School Board. The number was expanded to six persons in April, 1959, at which time Mr. Cornelius Hunt, Mr. Johnny Landrum, Mr. Willie Clay, and Mr. Carl L. Wilson joined Pilgrim and Mitchum on the board. The Advisory Board was instrumental in helping Ninth Avenue progress. For example, it was with the counsel of the Advisory Board that in 1960 a new addition to Ninth Avenue was constructed. The new addition housed the cafeteria, the band room and several new classrooms. Other issues, such as the education of the children of migrant workers temporarily living in Henderson County during harvest time, were brought before the board. The Hendersonville School Board decided during the period of 1958-1963 that quonset huts should be erected on the Ninth Avenue property to serve the educational needs of the migrant children. The Advisory Board continued to work with the school board through the process of desegregation in 1965, after which time the Advisory Board was discontinued.

After John Marable left as principal in 1959, four principals followed in six years. They were: Mr. Cedric Jones; Mr. William Gordon; Mr. J. R. Wright; and Mr. Leon Henry Anderson. The inexorable process of desegregation was now gaining momentum, and it was just a matter of time before the students of Ninth Avenue would be incorporated into the formally all-white schools of Hendersonville and Henderson County. (For a more complete recounting of the desegregation of the Henderson County schools, see Chapter One under the Community Council.) In 1962, sixty students from Transylvania County pulled out of the union school and began attending the public schools in Brevard, N.C., greatly diminishing the number of students at Ninth Avenue. In 1963, with the numbers down and integration becoming a certainty, several Ninth Avenue parents petitioned the school board to allow their children to attend the Hendersonville City Schools during that school year. The petition was at first put on hold by the Hendersonville School Board, but the parents took their case to the courts and subsequent pressure from the federal judicial system held the school system accountable to the law of the land. A contract of good faith was drawn up between the Ninth Avenue parents and the Hendersonville School Board with the expressed intention that total integration would take place in the Fall of 1965. This agreement was upheld by the courts. The last graduating class (16 students) from Ninth Avenue School held its commencement on May 27, 1965, and with that event the last vestiges of “separate but equal” came to an end in Henderson County. The Ninth Avenue School became a Junior High School in 1966 for children of all races.

After the Henderson County school system was desegregated there remained the issue of what to do about rehiring the teachers from Ninth Avenue as teachers in the newly integrated schools. Mrs. Mary Mims, a teacher from Ninth Avenue, recalled in 1986 in a taped interview, that the teachers from Ninth Avenue were called into an interview with Mr. Lockaby, the principal of Eighth Avenue High School (later, Hendersonville High School), but that in her view it had already been decided beforehand who would be selected to teach. Mrs. Mims and Mrs. Edwards were transferred from Ninth Avenue to Eighth Avenue and Mrs. Dusenberry was appointed as a librarian at Rosa Edwards School. “Unfortunately, there were many other Black teachers who were not placed, and that created quite a problem,” she said. Supported by the North Carolina Teacher Association, a class action lawsuit was filed by Julius Chambers, a lawyer from Charlotte, on June 25, 1965, on behalf of three of the teachers who were not rehired. Judge Braxton Craven, reviewing the case in his chambers, ruled that the board had not discriminated in its hiring practices. His ruling was eventually overturned by the Circuit Court of Appeals. The revised ruling ordered that all the teachers from Ninth Avenue be rehired. Out of all the teachers who lost their jobs due to desegregation, four of the Ninth Avenue teachers returned to teach in the Hendersonville schools and were granted retroactive pay.

There is a fondness for Ninth Avenue in the memory of those who attended. The students were known and cared about by the teachers and administrators, and in spite of other hardships, Black education thrived. This kind of quality in education at Ninth Avenue trained many outstanding students, some of whom are:

Medical Doctor:

Cornell T. Cooley, Jr. * Fayetteville NC

Doctors of Dentistry:

Oliver Summey Jr. * Washington DC

James Pilgrim, Jr. * Fayetteville NC

PhD’s:

Harold Powell * Chemistry – DuPont

William Alexander Darity * Amherst MA

Robert Copeland * University of Illinois

Optometrist:

Armond Edwards * Ft Pierce Florida

Attorneys:

Douglas Canty * Charlotte NC

Yvonne Mims Evans * Charlotte NC

Theodore Stephens * Oak Park MI

Gwendolyn S. Davis * Washington DC

Educators:

Betty Lou Payne * Rocky Mount NC

Mary S. Briggs * Winston-Salem NC

Joan Cooley * Cassapolis MI

Dora C. Brown * Cassapolis MI

Sarah S. Mitchell

From A Brief History of the Black Presence in Henderson County by Gary Franklin Green