The Community Council

In the early 1960’s Henderson County’s Community Council successfully pressed for the desegregation of schools and other reforms.

Excerpt from A Brief History of the Black Presence in Henderson County by Gary Franklin Green

The year was 1960. The Civil Rights movement had given a new voice to Black Americans, empowering many to speak out against the intolerable conditions of segregation in the South. North Carolina had long observed a division between the races in everyday life. In Henderson County in 1960, the public drinking fountains and rest rooms at the courthouse and city hall were segregated. Blacks weren’t allowed to eat at the lunch counters at local drug stores and restaurants, or spend the night at a hotel that was not Black-owned. There were still very few Blacks employed on Main Street and good jobs for Black people in factories were non-existent. This system could not long sustain itself and one by one people began to stand up and say, “This isn’t right.” Just as there were leaders emerging on the national scene to confront these evils, Henderson County had its own leaders who united to challenge a dying system and usher in a new day. The new system took shape primarily through the efforts of a local group of people who called themselves the Community Council of Henderson County.

Many of the national leaders of the Civil Rights Movement were from the Black church and the same was true for Henderson County. Rev. G. E. Weaver, pastor of the Star of Bethel Baptist Church, was a driving force in the establishment of the Community Council. Rev. Weaver was a much loved and socially minded leader who had been the minister of the Star of Bethel Baptist Church for ten years. He was able to inspire his congregation spiritually and socially by his sincere Christian vocation and his interest in improving the community. On November 14,1960, in the first recorded minutes of the Community Council, Rev. Weaver was elected to lead the Community Council as its President. It was on this date that a Constitution Committee was appointed with Mr. Cedric H. Jones being elected Chairman. It was the Constitution Committee’s responsibility to draw up a Constitution that would state the purposes for the group as well as structure the guidelines. It took three months for the Constitution Committee to complete its work, and when done the stated purpose for the Community Council was to “foster sentiment favorable to the growth, development and improvement of living conditions in Henderson County; and to cooperate with other civic, educational and fraternal organizations and agencies whose objectives and purposes are similar to the objectives and purposes of this organization.” Like the Society of Necessity, it was the good of the community that was paramount in the vision of the Community Council. Unlike the Society of Necessity, the issues were now more far-reaching and political in scope. There would be meetings with mayors, city councils, school boards and lawyers in an effort to see that the Black citizens of Henderson County were heard. Over the course of the next five years (1960-1965) many issues pertinent to the community would be addressed: unfit housing, voter registration, the Teenage Center, tutorial initiatives, integration of the school system, desegregation of public facilities and lunch counters, employment training and opportunities, street paving, and even the plight of certain families that the Council could help. For those first few years of work, the Community Council saw the integration of the schools, the appointment of the first Black policeman in Hendersonville, greater access to employment on Main Street, the first Black workers to be hired in local factories, the paving of streets in Black neighborhoods, and the overall improvement in living conditions. As the swirl of change that was sweeping across the South blew its breath of reform into Henderson County, the Community Council was there as the voice of persistent reason on those issues that most affected the Black community.

From the beginning, the Community Council was a religiously ecumenical group that represented persons from all geographical areas of Hendersonville. The role the Community Council played as an advocate for reform was bolstered by this widespread support. (It should be noted, however, that Black support was not 100 percent. There were those who feared that involvement with the Community Council could threaten their jobs and put their security in jeopardy.) The Community Council went to great lengths to ensure that they followed responsible and reasonable approaches to their causes. There would be many who would play an important role in the leadership of the Community Council over the years, including Alberta Jowers, Sam Mills, Kathleen Williams, William King, Mills Campbell, James Pilgrim, Mrs. Albert Floyd, Ruth Clay and many others, all serving selflessly to see that the ideas of the Community Council were carried out. The leadership from the ministry included: Rev. J. D. Ellis, Rev. H. L. Marsh, Rev. Ulysses Lattimore, and, of course, Rev. G. E. Weaver. The guidance of these four ministers over the five years from 1960-1965 would give the Council leadership and direction towards its goals. Rev. Weaver, who is credited with being the first leader of the Community Council, was able to serve the group only for a little over a year before he was called to other work in Florida. Following Rev. Weaver’s initial role as leader, two other pastors, Rev. Marsh and Rev. Ellis, stepped in to carry on and further the causes of the Council with able and determined leadership.

A typical meeting would begin with the singing of a hymn or patriotic song followed by Scripture reading and prayer. After the minutes were read, there were committee reports. The committees included: The Public Relations Committee; the Grievance Committee; the Project Committee; the Educational Committee; the Program Committee; and the Executive Committee. The Executive Committee wielded the most influence since it was there that many of the ideas for action originated and the agenda for the public meetings was set. Represented on this committee were one representative from each residential section of the city and county, the retiring elected officers, and the present elected officers. After the committee reports were read, the program for the evening was presented, followed by an open forum to answer and address any questions that might arise. This was a time of public discussion in which the problems of the community were addressed. Examples of topics discussed ranged from the upkeep of the cemetery, the process for integrating the school system, ways to ensure employment at local plants, and how to get more young people involved in the Council’s activities. There was never any lack of topics for discussion. Some of the programs were of a more practical nature dealing with such matters as health maintenance, life insurance, wills and deeds, the kinds of issues that persons were needing to face in their day-to-day living. Much was presented and dealt with from 1960 through 1965, but of all that was done by the Council, the desegregation of the Henderson County and Hendersonville public schools would bring to the Community Council its most public notoriety and its most difficult challenge.

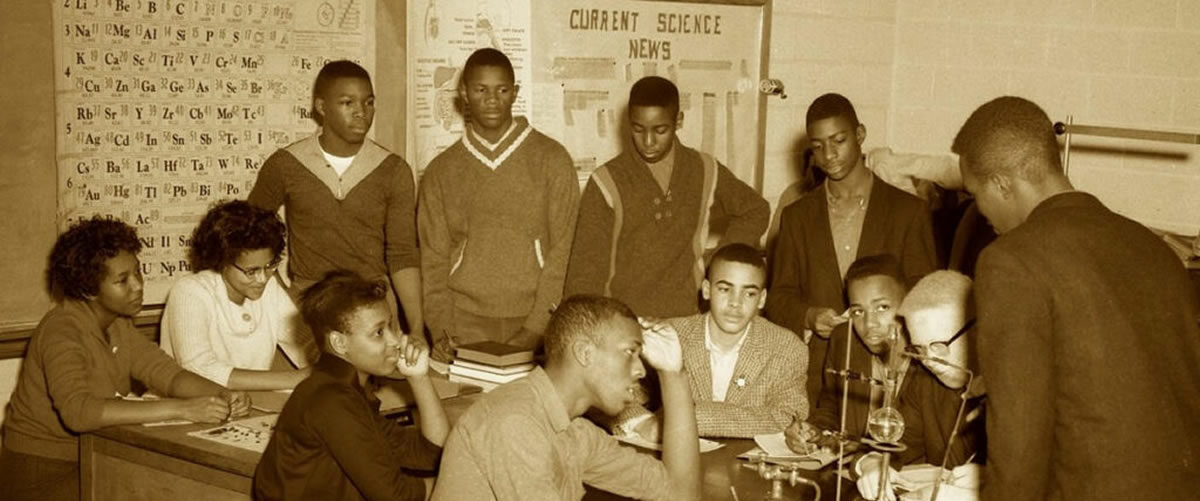

The year was 1963. The Ninth Avenue Graded School had served the educational needs of Black students from Polk, Transylvania, and Henderson counties for 15 years. But the institution of segregation had begun to crack. In 1962 the parents of students from Brevard, North Carolina, organized into a group called The Citizen and Improvement Organization. It was their goal to see that court-mandated desegregation of public schools in America be enacted immediately in the Brevard city schools. What rankled the parents and became the main point of contention was the excessively long bus ride that their children had to make daily to and from the Ninth Avenue School in Hendersonville. It was not unusual for a student from Transylvania County (where Brevard is located) to be on a school bus for over an hour each way. Taking into consideration the complaint of the parents, in 1962 the courts ordered the Brevard School System to integrate. In 1963, with many fewer students at Ninth Avenue School, the demand for school integration in Henderson County heightened and it was the Community Council that took up the cause. The Community Council’s goal was the desegregation of the Henderson County public schools and the method that they employed was to apply persistent pressure on the Hendersonville School Board until their goals were met.

The Community Council had already won a significant victory in 1961 by pushing the City and County Commissioners to eliminate separate drinking fountains and restrooms at the Hendersonville City Hall, the Henderson County Courthouse, and along Main Street. In fact, by 1962 the City had begun to show some support of the Council’s initiatives by allotting them a thousand dollars toward the heating system for the Teenage Center, a place for community youth to gather for activities and tutoring. As the barriers to equality began to fall, there was no doubt that changes were taking place in Henderson County. Still, there was a need to have someone or some group press the issue. Realizing this in regard to desegregation, the Council’s first step was to educate themselves in ways to peacefully and legally present their case. Leaders from Brevard’s Citizen and Improvement Organization met with members of the Council in January, 1963, relating how they had gone about their efforts at integration. Informing them of the need to “get their minds on the main points" and be willing to “push,” Mrs. Evon Kelly from Brevard stressed the need to organize, stay together and get legal help if necessary. Two months later, The American Friends Service Committee, a social outreach arm of the Quaker faith, also came to the Council to further encourage and instruct in desegregation options. After the meeting with the Friends, an Education Committee was formed that would become the focus for the desegregation strategies for the Council. The Committee consisted of Rev. Marsh, Rev. Ellis, Mrs. Alberta Floyd and Mrs. Kathleen Williams. It would be this Committee that would eventually confront the Hendersonville School Board with a legal suit demanding the desegregation of the public school system.

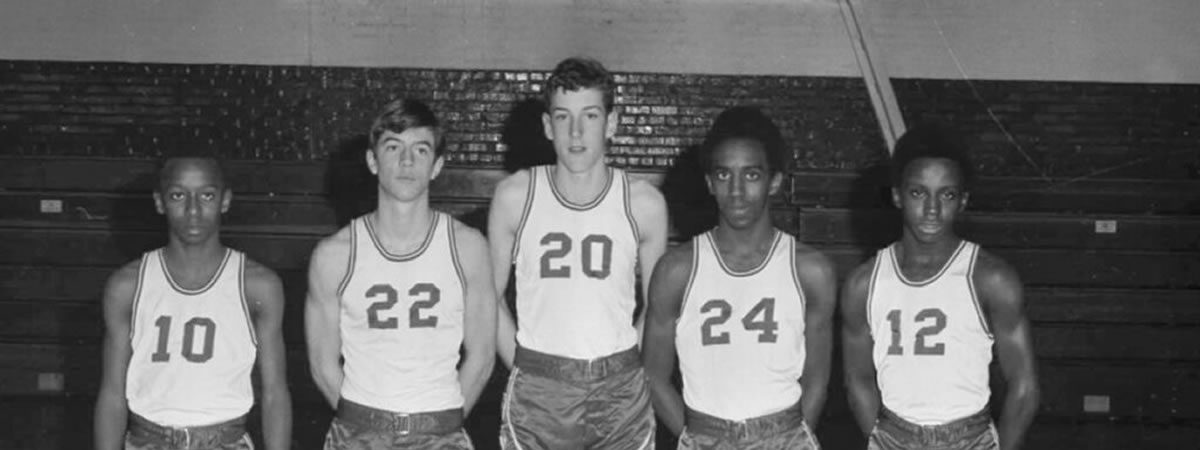

By 1964 the momentum for desegregation was growing. Everyone knew that it was coming but the question remained when. In Etowah, Frank and Viola Payne had successfully persuaded the School Board to admit her son Carlos to West Henderson High School for the 1964 school year. Mrs. Payne argued that it was now the law of the land and that she wanted a quality education for her son, adding that the bus ride to Ninth Avenue School was time consuming and therefore it would be better for the well being of her son that he attend a school closer to his home. With Rev. J. D. Ellis supporting her from the Community Council, she was granted her request, thus technically making Carlos Clark the first Black student to enroll in a previously all White school in Henderson County. Meanwhile at Hendersonville High School, the band director, Mr. Earl Martin, had commenced a cooperative project with the Ninth Avenue band members that would have far reaching consequences. This interracial band, according to the oral accounts of Mrs. Kathleen Williams, was a major step in orienting the students for the eventual process of integration. The students in the band knew and respected each other, so when the day of integration came in 1965, it would prove to be a smooth and uncomplicated process.

In 1963, the Council perceived there was still some foot- dragging on the part of the Hendersonville School Board in regard to integration. It was decided by the Council’s Education Committee that the time had come to hire professional help. A Black Civil Rights lawyer from Asheville by the name of Reuben Daley, who had a strong reputation for winning desegregation suits, was hired. A class action lawsuit was drawn up and filed in Western District Court against the Hendersonville School Board, demanding that the schools desegregate. The City of Hendersonville under the direction of Hugh D. Randall, the Superintendent of Schools, countered that it was negotiating in good faith by drawing up a plan to admit 65 black students into the school system by 1965. There were renovations being completed at the Rosa Edwards school and at that time, White schoolchildren were attending classes in the V. F. W. Hall. The court accepted this proposal from the Hendersonville School Board, as did the U.S. Department of Education, Health and Welfare. In June, 1965 the Ninth Avenue School held its last Commencement and in September of that year the Hendersonville City and Henderson County schools opened their doors to blacks for the first time, thus ending the system of “separate but equal” forever.

In a letter to the School Board on behalf of the Community Council, Rev. J. D. Ellis stated:

“In view of the many changes which are being brought about in our lives educationally, we recognize the fact that it takes much foresight, much planning and much prayer in order to reach decisions that will best benefit all concerned. We, therefore, wish to commend you for your recent decision to reorganize the city school system on an integrated basis, and pledge our support to help in any way possible.”

In some ways this ended the most controversial chapter in the history of the Community Council. The Council continued to meet until the late 1970’s, but those five years leading up to the integration of the school system were the most fruitful. Never again would the Black community lack recognition in their efforts to improve the lives of its people in Henderson County. The Council proved that it could work for the community and get results. The charitable nature of the Council’s intentions never wavered, nor did its resolve, as it strove to right the wrongs of segregation.

From A Brief History of the Black Presence in Henderson County by Gary Franklin Green